1. Transmisión directa:

a) Transmisión horizontal

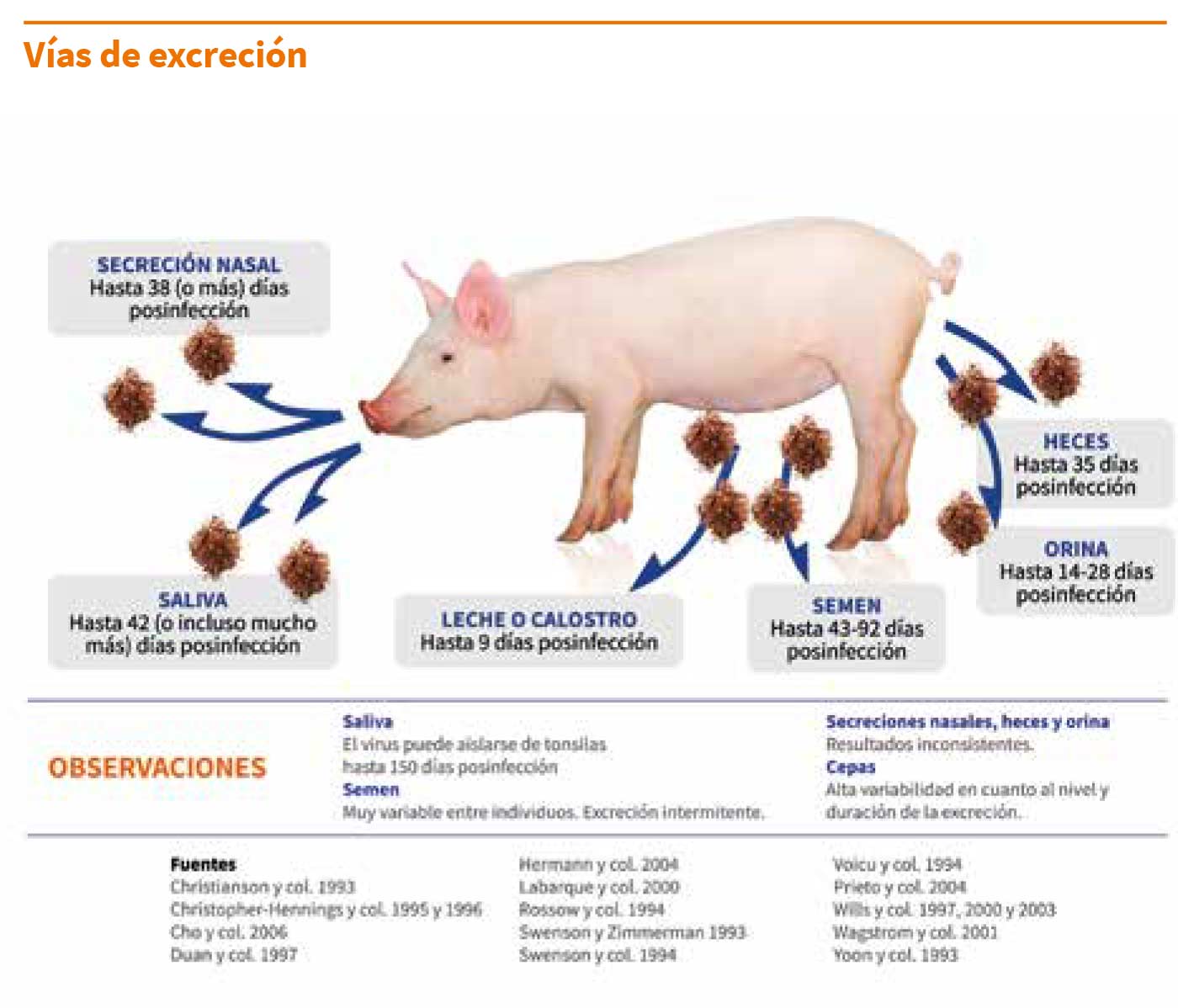

a.1) Vías de excreción:

Los cerdos infectados pueden excretar el virus por múltiples vías y durante un largo periodo de tiempo; principalmente por la saliva y el semen; de forma menos frecuente por la leche y el calostro, y raramente y de forma esporádica por las secreciones nasales, orina y heces.

La cantidad de virus excretado, junto a la duración de la excreción, varía de forma significativa entre cepas.

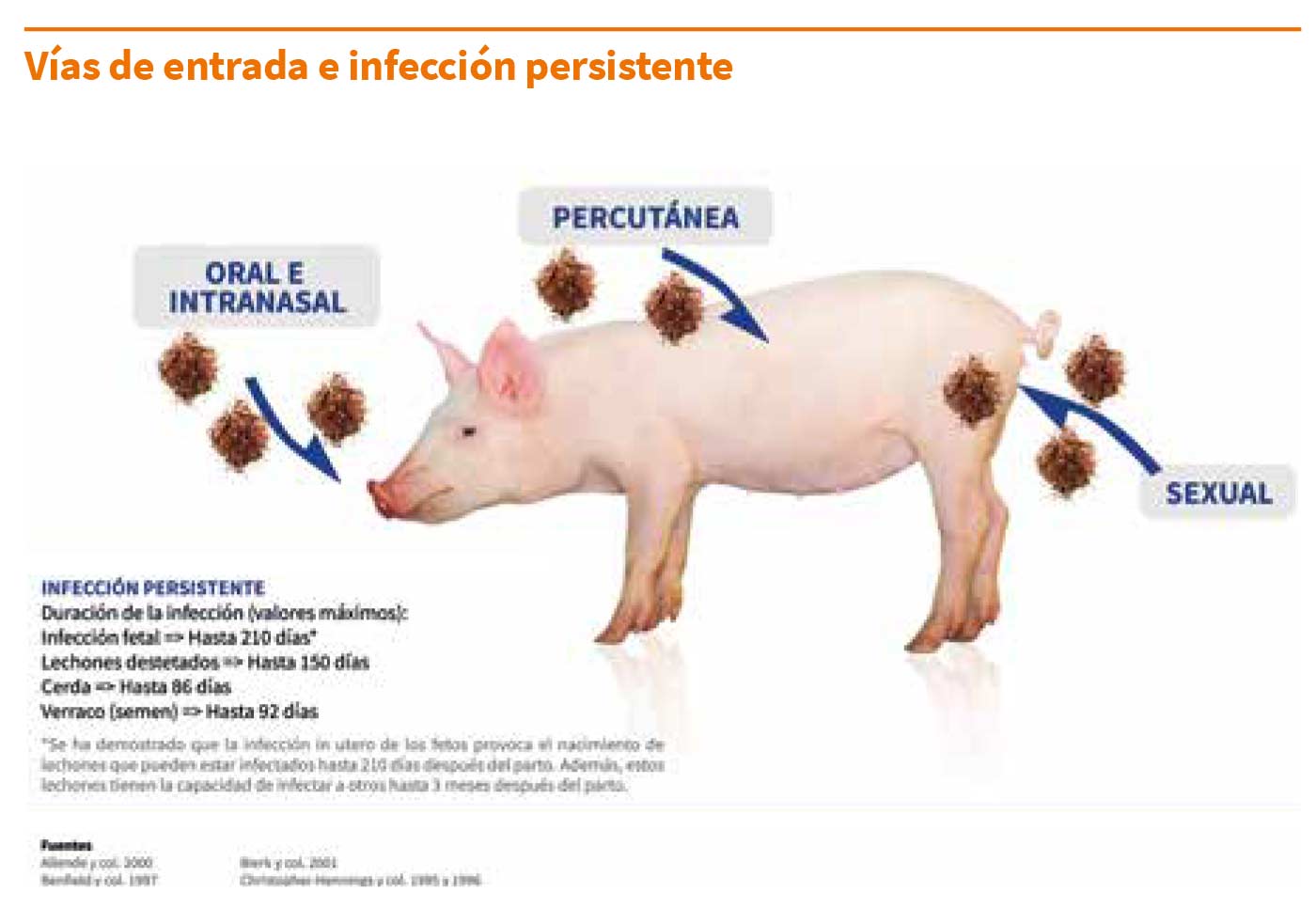

a.2) Vías de entrada:

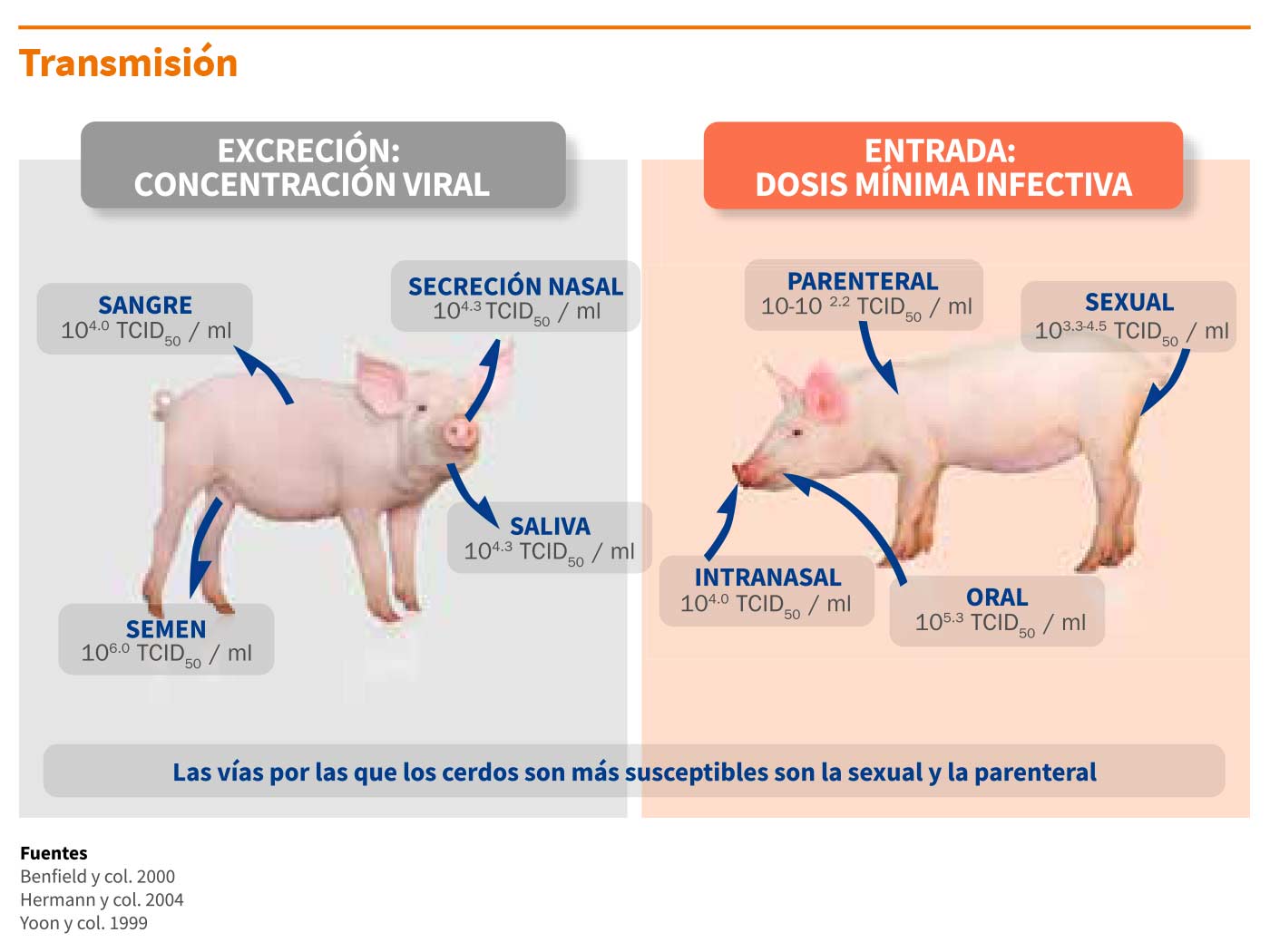

Los cerdos pueden infectarse por varias vías, incluyendo la oral, la intranasal, la parenteral y la sexual (intrauterina y vaginal).

La probabilidad de infectarse depende en gran medida de la vía y de la dosis. Además, se han observado diferencias entre cepas para todas las vías de transmisión.

a.3) Infección crónica/persistente (animales portadores):

El virus puede detectarse en la sangre durante largos periodos de tiempo.

La duración de la viremia está marcadamente influenciada por la cepa y la edad del animal. Así, puede durar semanas en lechones (hasta 90 días), mientras que en adultos puede desaparecer en tan sólo unos días.

Tras la viremia, el virus puede persistir durante semanas en el animal, principalmente en tonsilas y otros tejidos linfoides.

Aunque la mayoría de cerdos eliminan el virus en 90-120 días, algunos quedan persistentemente infectados durante meses (el virus puede aislarse de tonsilas hasta 150 días después). La infección persistente ocurre en todas las edades, pero los valores máximos se han observado en fetos infectados in utero.

Se ha sugerido que la persistencia del virus implica una continua replicación, por lo que no puede considerarse como un estado real de infección persistente.

Obviamente, la viremia prolongada y la infección persistente incrementan la posibilidad de transmisión. Tal y como ocurre con otros miembros de la familia Arteriviridae, los cerdos que ya no son virémicos y/o han superado la fase aguda pueden seguir excretando el virus del PRRS a bajos niveles y/o de forma intermitente. Por tanto, un resultado negativo en la detección del virus en sangre en animales previamente infectados, no nos permite descartar totalmente que el animal pueda excretar el virus.

Por tanto, un resultado negativo de viremia o anticuerpos séricos en un cerdo previamente infectado no descarta que el animal pueda estar excretando el virus.

a.4) Importancia del semen en la transmisión del virus del PRRS:

El semen puede desempeñar un papel crucial en la transmisión de este virus. Esto es así debido al uso generalizado de la inseminación artificial y a las características específicas del virus excretado por esta vía.

A modo de ejemplo, la cantidad de virus necesaria para infectar por vía sexual a una cerda susceptible suele ser muy inferior a la cantidad de virus presente en el semen de un verraco infectado.

A pesar de que la viremia en verracos suele ser muy corta, de unos pocos días a máximo dos-tres semanas, estos pueden excretar el virus en semen durante semanas.

El virus se ha podido aislar de la glándula bulbouretral de los verracos hasta tres meses posinfección. Este hecho sugiere que el tracto reproductivo podía tener un papel muy significativo en la persistencia del virus.

Por tanto, la viremia no es un indicador adecuado de si o no existe excreción del virus.

De todas formas, parece que la transmisión a través del semen ocurre de forma más habitual en los primeros días de la infección, cuando los títulos de virus en semen son mayores.

Aquí, cabe destacar que existe una elevada variabilidad entre verracos, y que estos pueden excretar el virus de forma intermitente.

En consecuencia, un resultado aislado negativo de PCR a partir de suero o semen no nos permite descartar la posibilidad de que el animal excrete el virus por esta vía; debería analizarse más de una muestra de un mismo verraco en diferentes periodos.

a.5) Vía de entrada parenteral:

Los cerdos son extremadamente susceptibles a la infección por vía parenteral. De hecho, son necesarias muy pocas partículas del virus del PRRS para infectar a un cerdo por esta vía (10-102.2 TCID50/ml).

Por lo tanto, cualquier evento, práctica o material contaminado que pueda afectar la integridad de la barrera cutánea, puede facilitar la transmisión del virus, como por ejemplo: corte de dientes, crotalado de orejas, cortes de colas, inoculaciones con medicamentos (agujas) , etc.

La infección puede ocurrir a través de la reutilización de una aguja que previamente ha sido usada para vacunar a cerdos infectados. Además, como el virus está presente en los fluidos orales de manera constante, el comportamiento social normal de los cerdos y las interacciones agresivas (mordeduras, arañazos, abrasiones…) también pueden provocar una infección parenteral.

b) transmisión vertical:

Las cerdas pueden transmitir el virus a su descendencia por contacto directo (transmisión horizontal) y/o por vía transplacentaria (transmisión vertical).

En relación a la transmisión vertical, el virus puede atravesar la barrera placentaria de manera eficiente en el último tercio de la gestación. Como resultado, los fetos pueden morir. Alternativamente, los lechones que sobreviven generalmente nacen débiles y permanecen infectados.

Como hemos indicado anteriormente, los lechones infectados durante la fase fetal podrían permanecer positivos durante mucho tiempo e infectar a otros lechones hasta tres meses después del parto, contribuyendo a la propagación de la infección.

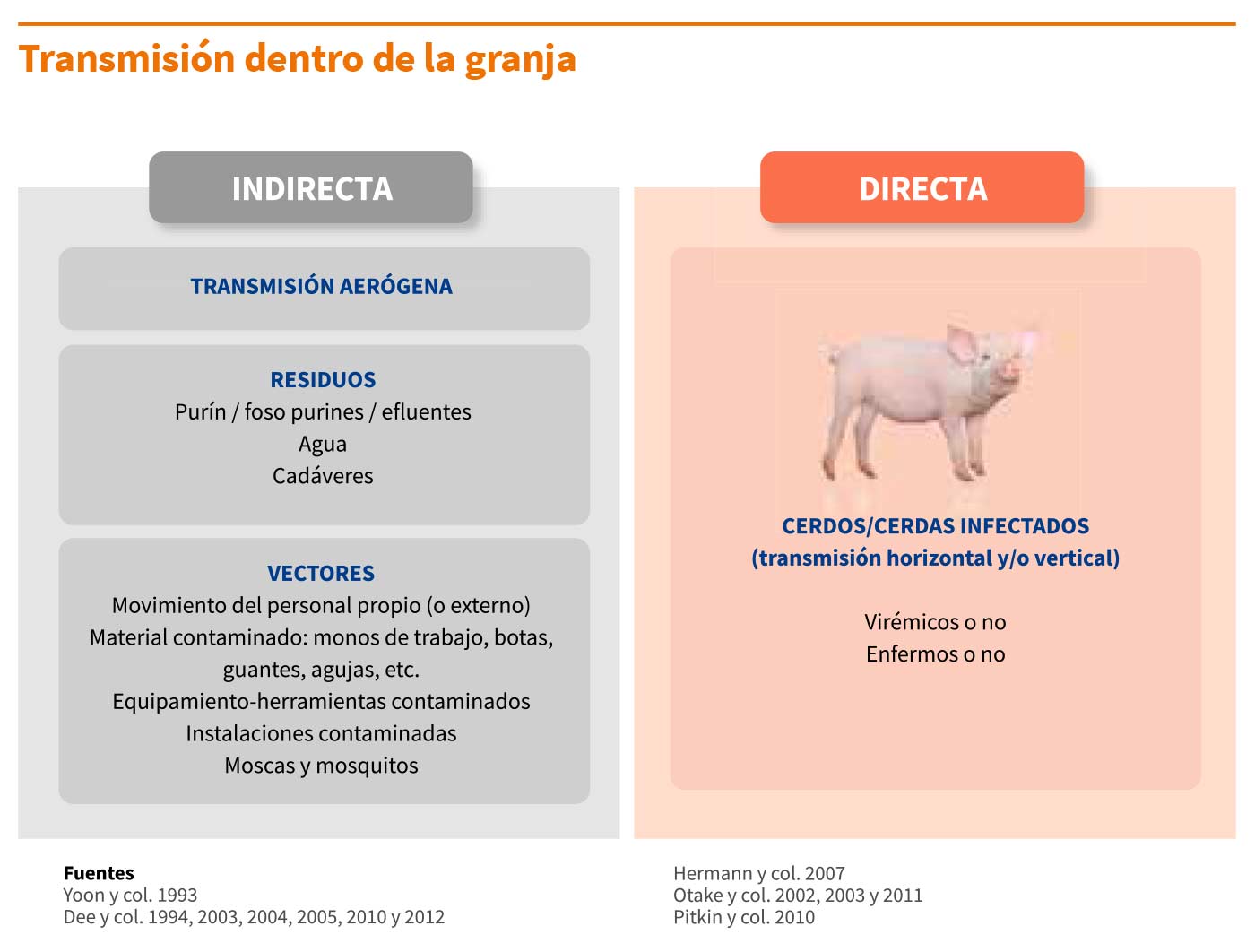

2. Transmisión indirecta:

Se han demostrado varias vías de transmisión indirecta por fómites y residuos contaminados, así como la transmisión por aire (consultar el punto “Transmisión entre granjas”).

Dentro de la granja, debemos prestar especial atención a las manos/guantes, monos de trabajo, botas, y principalmente a las agujas, ya que los cerdos son extremadamente susceptibles a la infección por vía parenteral.

© Laboratorios Hipra, S.A. 2024. Reservados todos los derechos.

Ninguna parte de este sitio web o cualquiera de sus contenidos puede ser reproducida, copiada, modificada o adaptada, sin el consentimiento previo por escrito de HIPRA.

- Albina E. Epidemiology of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS): an overview. Vet Microbiol. 1997, 55:309-16.

- Albina E, Carrat C, Charley B. Interferon-alpha response to swine arterivirus (PoAV), the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1998, 18:485-90.

- Allende R, Laegreid WW, Kutish GF, Galeota JA, Wills RW, Osorio FA. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: description of persistence in individual pigs upon experimental infection. J Virol. 2000, 74:10834-7.

- Andino R, Domingo E. Viral quasispecies. 2015, 479-480C:46-51.

- Arruda AG, Friendship R, Carpenter J, Hand K, Ojkic D, Poljak Z. Investigation of the Occurrence of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Virus in Swine Herds Participating in an Area Regional Control and Elimination Project in Ontario, Canada. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2015, Mar 11.

- Benfield DA, Christopher-Hennings J, Nelson EA, Rowland RR. , Nelson JK, Chase CL, Rossow KD, Collins JE. Persistent fetal infection of PRRS virus. In Proceedings of the28th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Swine. 1997: 455-8.

- Benfield D, Nelson J, Rossow K, Nelson C, Steffen M, Rowland R. Diagnosis of persistent or prolonged porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infections. Vet Res. 2000, 31:71.

- Benfield DA, Nelson C, Steffen M, Rowland RRR. Transmission of PRRSV by artificial insemination using extended semen seeded with different concentrations of PRRSV. Proceeding of the American Association of Swine Practitioners. 2000:405-408.

- Bierk MD, Dee SA, Rossow KD, Otake S, Collins JE, Molitor TW. Transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus from persistently infected sows to contact controls. Can J Vet Res. 2001, 65:261-6.

- Blaha T. The «colorful» epidemiology of PRRS. Vet Res. 2000, 31:77-83.

- Brockmeier SL, Lager KM. Experimental airborne transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus and Bordetella bronchiseptica. Vet Microbiol. 2002, 89:267-75.

- Brito B, Dee SA, Wayne S, Alvarez J, Perez A. Genetic diversity of PRRS virus collected from air samples in four different regions of concentrated swine production during a high incidence season. Viruses. 2014, 6:4424-36.

- Charpin C, Mahé S, Keranflec’h A, Belloc C, Cariolet R, Le Potier MF, Rose N. Infectiousness of pigs infected by the Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome virus (PRRSV) is time-dependent. Vet Res.2012, 43:69.

- Cho JG, Dee SA, Deen J, Guedes A, Trincado C, Fano E, Jiang Y, Faaberg K, Collins JE, Murtaugh MP, Joo HS. Evaluation of the effects of animal age, concurrent bacterial infection, and pathogenicity of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus on virus concentration in pigs. Am J Vet Res. 2006, 67:489-93.

- Cho JG, Dee SA. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Theriogenology. 2006, 66:655-62.

- Cho JG, Deen J, Dee SA. Influence of isolate pathogenicity on the aerosol transmission of Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Can J Vet Res. 2007, 71:23-7.

- Christianson WT, Choi CS, Collins JE, Molitor TW, Morrison RB, Joo HS. Pathogenesis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection in mid-gestation sows and fetuses. Can J Vet Res. 1993, 57:262-8.

- Christopher-Hennings J, Nelson EA, Hines RJ, Nelson JK, Swenson SL, Zimmerman JJ, Chase CL, Yaeger MJ, Benfield DA. Persistence of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in serum and semen of adult boars. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1995, 7:456-64.

- Christopher-Hennings J, Nelson EA, Nelson JK, Hines RJ, Swenson SL, Hill HT, Zimmerman JJ, Katz JB, Yaeger MJ, Chase CC, et al. Detection of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in boar semen by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995, 33:1730-4.

- Christopher-Hennings J, Nelson EA, Benfield DA. Detecting PRRSV in boar semen. Swine Health and Production. 1996, 4:37-9.

- Christopher-Hennings J, Nelson EA, Nelson JK, Benfield DA. Effects of a modified-live virus vaccine against porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome in boars. Am J Vet Res. 1997, 58:40-5.

- Christopher-Hennings J. The pathogenesis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in the boar. Vet Res. 2000, 31:57-8.

- Christopher-Hennings J. Monitoring for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in the boar stud. J Swine Health Prod. 2001, 9:186-8.

- Christopher-Hennings J, Holler LD, Benfield DA, Nelson EA. Detection and duration of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in semen, serum, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and tissues from Yorkshire, Hampshire, and Landrace boars. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2001, 13:133-42.

- Corzo CA, Mondaca E, Wayne S, Torremorell M, Dee S, Davies P, Morrison RB. Control and elimination of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus Res. 2010, 154:185-92.

- Cutler TD, Wang C, Hoff SJ, Kittawornrat A, Zimmerman JJ. Median infectious dose (ID₅₀) of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolate MN-184 via aerosol exposure. Vet Microbiol. 2011, 151:229-37.

- Dee SA, Joo HS. Prevention of the spread of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in endemically infected pig herds by nursery depopulation. Vet Rec. 1994, 135:6-9.

- Dee SA, Deen J, Rossow K, Wiese C, Otake S, Joo HS, Pijoan C. Mechanical transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus throughout a coordinated sequence of events during cold weather. Can J Vet Res. 2002, 66:232-9.

- Dee S, Deen J, Rossow K, Weise C, Eliason R, Otake S, Joo HS, Pijoan C. Mechanical transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus throughout a coordinated sequence of events during warm weather. Can J Vet Res. 2003, 67:12-9.

- Dee SA, Deen J, Otake S, Pijoan C. An experimental model to evaluate the role of transport vehicles as a source of transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus to susceptible pigs. Can J Vet Res. 2004, 68:128-33.

- Dee SA, Martinez BC, Clanton C. Survival and infectivity of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in swine lagoon effluent. Vet Rec. 2005, 156:56-7.

- Dee SA, Cano JP, Spronk G, Reicks D, Ruen P, Pitkin A, Polson D. Evaluation of the long-term effect of air filtration on the occurrence of new PRRSV infections in large breeding herds in swine-dense regions. Viruses. 2012, 4:654-62.

- De Jong MC, Kimman TG. Experimental quantification of vaccine-induced reduction in virus transmission. Vaccine. 1994, 12:761–766.

- DiekmannO, Heesterbeek JA, Metz JA. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio R0 in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. J Math Biol. 1990, 28:365-82.Duan X, Nauwynck HJ, Pensaert MB. Virus quantification and identification of cellular targets in the lungs and lymphoid tissues of pigs at different time intervals after inoculation with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). Vet Microbiol. 1997, 56:9-19.

- Goldberg TL, Lowe JF, Milburn SM, Firkins LD. Quasispecies variation of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus during natural infection. Virology. 2003, 317:197-207.

- Guarino H, Cox RB, Goyal SM, Patnayak DP. Survival of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus in Pork Products. Food Environ Virol. 2013 Jun 13.

- Hall W, Neumann E. Fresh Pork and Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus: Factors Related to the Risk of Disease Transmission. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2013 Sep 10.

- Hermann JR, Muñoz-Zanzi CA, Roof MB, Burkhart K, Zimmerman JJ. Probability of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus infection as a function of exposure route and dose. Vet Microbiol. 2005, 110:7-16.

- Hermann JR, Hoff S, Muñoz-Zanzi C, Yoon KJ, Roof M, Burkhardt A, Zimmerman J. Effect of temperature and relative humidity on the stability of infectious porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in aerosols. Vet Res. 2007, 38:81-93.

- Hooper CC, Van Alstine WG, Stevenson GW, Kanitz CL. Mice and rats (laboratory and feral) are not a reservoir for PRRS virus. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1994, 6:13-5.

- Kappes MA, Faaberg KS. PRRSV structure, replication and recombination: Origin of phenotype and genotype diversity. Virology. 2015, 479-480:475-86.

- Karniychuk UU, Saha D, Geldhof M, Vanhee M, Cornillie P, Van den Broeck W, Nauwynck HJ. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) causes apoptosis during its replication in fetal implantation sites. Microb Pathog. 2011, 51:194-202.

- Karniychuk UU, Nauwynck HJ. Pathogenesis and prevention of placental and transplacental porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection. Vet Res. 2013, 44:95.

- Klinkenberg, D, de Bree, J, Laevens, H, de Jong, MC, Within- and

between-pen transmission of Classical Swine Fever Virus: a new method to

estimate the basic reproduction ratio from transmission experiments. Epidemiol. Infect. 2002, 128: 293–299.Kristensen CS, Bøtner A, Takai H, Nielsen JP, Jorsal SE. Experimental airborne transmission of PRRS virus. Vet Microbiol. 2004, 99:197-202. - Labarque GG, Nauwynck HJ, Van Reeth K, Pensaert MB. Effect of cellular changes and onset of humoral immunity on the replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in the lungs of pigs. J Gen Virol. 2000, 81:1327-34.

- Larochelle R1, D’Allaire S, Magar R. Molecular epidemiology of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in Québec. Virus Res. 2003, 96:3-14.

- Le Potier MF, Blanquefort P, Morvan E, Albina E. Results of a control programme for the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome in the French ‘Pays de la Loire’ region. Vet Microbiol. 1997, 55:355-60.

- Magar R, Larochelle R, Dea S, Gagnon CA, Nelson EA, Christopher-Hennings J, Benfield DA. Antigenic comparison of Canadian and US isolates of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus using monoclonal antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein. Can J Vet Res. 1995, 59:232-4.

- Martín-Valls GE, Kvisgaard LK, Tello M, Darwich L, Cortey M, Burgara-Estrella AJ, Hernández J, Larsen LE, Mateu E. Analysis of ORF5 and full-length genome sequences of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates of genotypes 1 and 2 retrieved worldwide provides evidence that recombination is a common phenomenon and may produce mosaic isolates. J Virol. 2014, 88:3170-81.

- Mondaca-Fernández E, Meyns T, Muñoz-Zanzi C, Trincado C, Morrison RB. Experimental quantification of the transmission of Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome Can J Vet Res. 2007, 71:157-60.

- Nodelijk G, de Jong MC, Van Nes A, Vernooy JC, Van Leengoed LA, Pol JM, Verheijden JH. Introduction, persistence and fade-out of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in a Dutch breeding herd: a mathematical analysis. Epidemiol Infect.2000, 124: 173-82.

- Nodelijk G, de Jong MC, van Leengoed LA, Wensvoort G, Pol JM, Steverink PJ, Verheijden JH. A quantitative assessment of the effectiveness of PRRSV vaccination in pigs under experimental conditions. 2001, 19:3636-44.

- Nodelijk G. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) with special reference to clinical aspects and diagnosis. A review. Vet Q. 2002, 24:95-100.

- Nodelijk G, Nielen M, De Jong MC, Verheijden JH. A review of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in Dutch breeding herds: population dynamics and clinical relevance. Prev Vet Med. 2003, 60:37-52.

- Otake S, Dee SA, Rossow KD, Joo HS, Deen J, Molitor TW, Pijoan C. Transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus by needles. Vet Rec. 2002, 150:114-5.

- Otake S, Dee SA, Rossow KD, Moon RD, Trincado C, Pijoan C. Transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus by houseflies (Musca domestica). Vet Rec. 2003, 152:73-6.

- Otake S, Dee SA, Moon RD, Rossow KD, Trincado C, Farnham M, Pijoan C. Survival of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in houseflies. Can J Vet Res. 2003, 67:198-203.

- Otake S, Dee SA, Moon RD, Rossow KD, Trincado C, Pijoan C. Evaluation of mosquitoes, Aedes vexans, as biological vectors of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Can J Vet Res. 2003, 67:265-70.

- Otake S, Dee S, Corzo C, Oliveira S, Deen J. Long-distance airborne transport of infectious PRRSV and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae from a swine population infected with multiple viral variants. Vet Microbiol. 2010, 145:198-208.

- PileriE, Gibert E, Soldevila F, García-Saenz A, Pujols J, Diaz I, Darwich L, Casal J, Martín M, Mateu E. Vaccination with a genotype 1 modified live vaccine against porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus significantly reduces viremia, viral shedding and transmission of the virus in a quasi-natural experimental model. Vet Microbiol. 2015, 175:7-16.

- PileriE, Mateu E. Review on the transmission porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus between pigs and farms and impact on vaccination. Vet Res. 2016, 47:108.

- PileriE, Martín-Valls GE, Díaz I, Allepuz A, Simon-Grifé M, García-Saenz A, Casal J, Mateu E. Estimation of the transmission parameters for swine influenza and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses in pigs from weaning to slaughter under natural conditions. Prev Vet Med. 2017a, 138:147-155.

- PileriE, Gibert E, Martín-Valls GE, Nofrarias M, López-Soria S, Martín M, Díaz I, Darwich L, Mateu E. Transmission of Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus 1 to and from vaccinated pigs in a one-to-one model. Vet Microbiol. 2017b, 201:18-25.

- Pirtle EC, Beran GW. Stability of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in the presence of fomites commonly found on farms. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1996, 208:390-2.

- Pitkin A, Deen J, Dee S. Further assessment of fomites and personnel as vehicles for the mechanical transport and transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Can J Vet Res. 2009, 73:298-302.

- Prieto C, García C, Simarro I, Castro JM. Temporal shedding and persistence of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in boars. Vet Rec. 2004, 154:824-7.

- Prieto C, Castro JM. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection in the boar: a review. Theriogenology. 2005, 63:1-16.

- Romagosa A, Allerson M, Gramer M, Joo HS, Deen J, Detmer S, Torremorell M. Vaccination of influenza a virus decreases transmission rates in pigs. Vet Res. 2011;42:120.

- RoseN, Renson P, Andraud M, Paboeuf F, Le Potier MF, Bourry O. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSv) modified-live vaccine reduces virus transmission in experimental conditions. 2015, 33:2493-9.

- Rossow KD, Bautista EM, Goyal SM, Molitor TW, Murtaugh MP, Morrison RB, Benfield DA, Collins JE. Experimental porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection in one-, four-, and 10-week-old pigs. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1994, 6:3-12.

- Rossow KD, Collins JE, Goyal SM, Nelson EA, Christopher-Hennings J, Benfield DA. Pathogenesis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection in gnotobiotic pigs. Vet Pathol. 1995, 32:361-73.

- Rowland RR, Steffen M, Ackerman T, Benfield DA. The evolution of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: quasispecies and emergence of a virus subpopulation during infection of pigs with VR-2332. Virology. 1999, 259:262-6.

- Schurrer JA, Dee SA, Moon RD, Murtaugh MP, Finnegan CP, Deen J, Kleiboeker SB, Pijoan CB. Retention of ingested porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in houseflies. Am J Vet Res. 2005, 66:1517-25.

- Snijder EJ, Kikkert M, Fang Y. Arterivirus molecular biology and pathogenesis. J Gen Virol. 2013, 94:2141-63.

- Swenson SL, Zimmerman J. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in experimentally infected boars: isolation from semen. In Proceedings of the American Association of Swine Practitioners. 1993, 719-20.

- Swenson SL, Hill HT, Zimmerman JJ, Evans LE, Landgraf JG, Wills RW, Sanderson TP, McGinley MJ, Brevik AK, Ciszewski DK, et al. Excretion of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in semen after experimentally induced infection in boars. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1994, 204:1943-8.

- Torremorell M, Pijoan C, Janni K, Walker R, Joo HS. Airborne transmission of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in nursery pigs. Am J Vet Res. 1997, 58:828-32.

- Voicu IL, Silim A, Morin M, Elazhary MASY. Interaction of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus with swine monocytes. Vet Rec. 1994, 134:422-423.

- Yoon IJ, Joo HS, Christianson WT, et al. Persistent and contact infection in nursery pigs experimentally infected with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus. Swine Health and Production. 1993, 1:5-8.

- VelthuisAG, de Jong MC, de Bree J, Nodelijk G, van Boven M. Quantification of transmission in one-to-one experiments. Epidemiol Infect. 2002, 128, 193-204.

- Wagstrom EA, Chang CC, Yoon KJ, Zimmerman JJ. Shedding of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in mammary gland secretions of sows. Am J Vet Res. 2001, 62:1876-80.

- Wills RW, Zimmerman JJ, Yoon KJ, Swenson SL, McGinley MJ, Hill HT, Platt KB, Christopher-Hennings J, Nelson EA. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: a persistent infection. Vet Microbiol. 1997, 55:231-40.

- Wills RW, Zimmerman JJ, Yoon KJ, Swenson SL, Hoffman LJ, McGinley MJ, Hill HT, Platt KB. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: routes of excretion. Vet Microbiol. 1997, 57:69-81.

- Wills RW, Doster AR, Galeota JA, Sur JH, Osorio FA. Duration of infection and proportion of pigs persistently infected with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Clin Microbiol. 2003, 41:58-62.

- Wyckoff AC, Henke SE, Campbell TA, Hewitt DG, VerCauteren KC. Feral swine contact with domestic swine: a serologic survey and assessment of potential for disease transmission. J Wildl Dis. 2009, 45:422-9.

- Zimmerman JJ, Yoon KJ, Wills RW, Swenson SL. General overview of PRRSV: a perspective from the United States. Vet Microbiol. 1997, 55:187-96.

Todos los derechos reservados. © HIPRA

Todos los derechos reservados. © HIPRA