La identificación del virus se puede lograr mediante la detección de proteínas virales (antígeno) o de ácidos nucleicos y mediante el aislamiento.

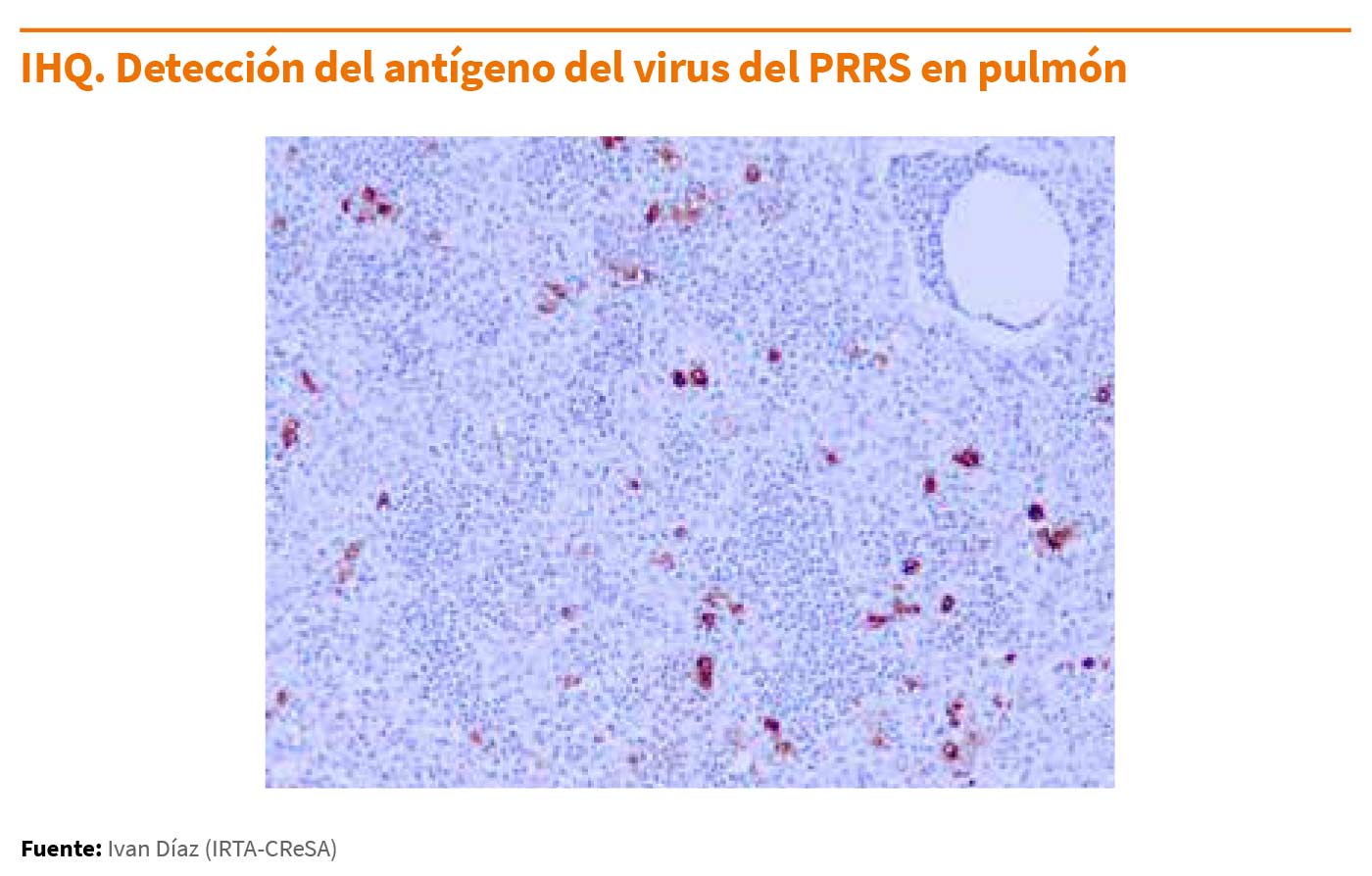

Inmunohistoquímica (IHQ) e hibridación in situ (HIS).

El antígeno y el ácido nucleico del virus del PRRS pueden detectarse en tejidos mediante IHQ o HIS, respectivamente. La relación entre la presencia del virus y las lesiones puede establecerse mediante una combinación de IHQ o HIS e histopatología.

Aislamiento y titulación del virus

Mientras que las cepas de PRRSV2 pueden aislarse tanto en cultivos de macrófagos alveolares porcinos como en sublíneas de la línea celular de riñón de mono africano (CL-2621 y MARC-145), muchos de los virus PRRSV1 o parecidos a los europeos se pueden aislar únicamente en macrófagos alveolares porcinos.

Dado que los efectos citopáticos, que ocurren en 1-4 días, no siempre son claros, la replicación del virus en los cultivos celulares generalmente debe confirmarse mediante RT-PCR, IPMA o IF (sensibilidad máxima a los 7 días). La titulación del virus se puede hacer usando diluciones en serie de la muestra.

Detección del genoma del virus

Fragmentos de restricción de longitud polimórfica (Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism; RFLP)

Implica la digestión de la ORF5 por tres enzimas de restricción. Como resultado, se genera un patrón de tres dígitos. Esta técnica se utiliza para diferenciar aislados. Sin embargo, se ha demostrado que diferentes aislados pueden compartir patrones de RFLP similares.

Por lo tanto, para diferenciar aislados la secuenciación (ver a continuación) es mejor que la técnica RFLP.

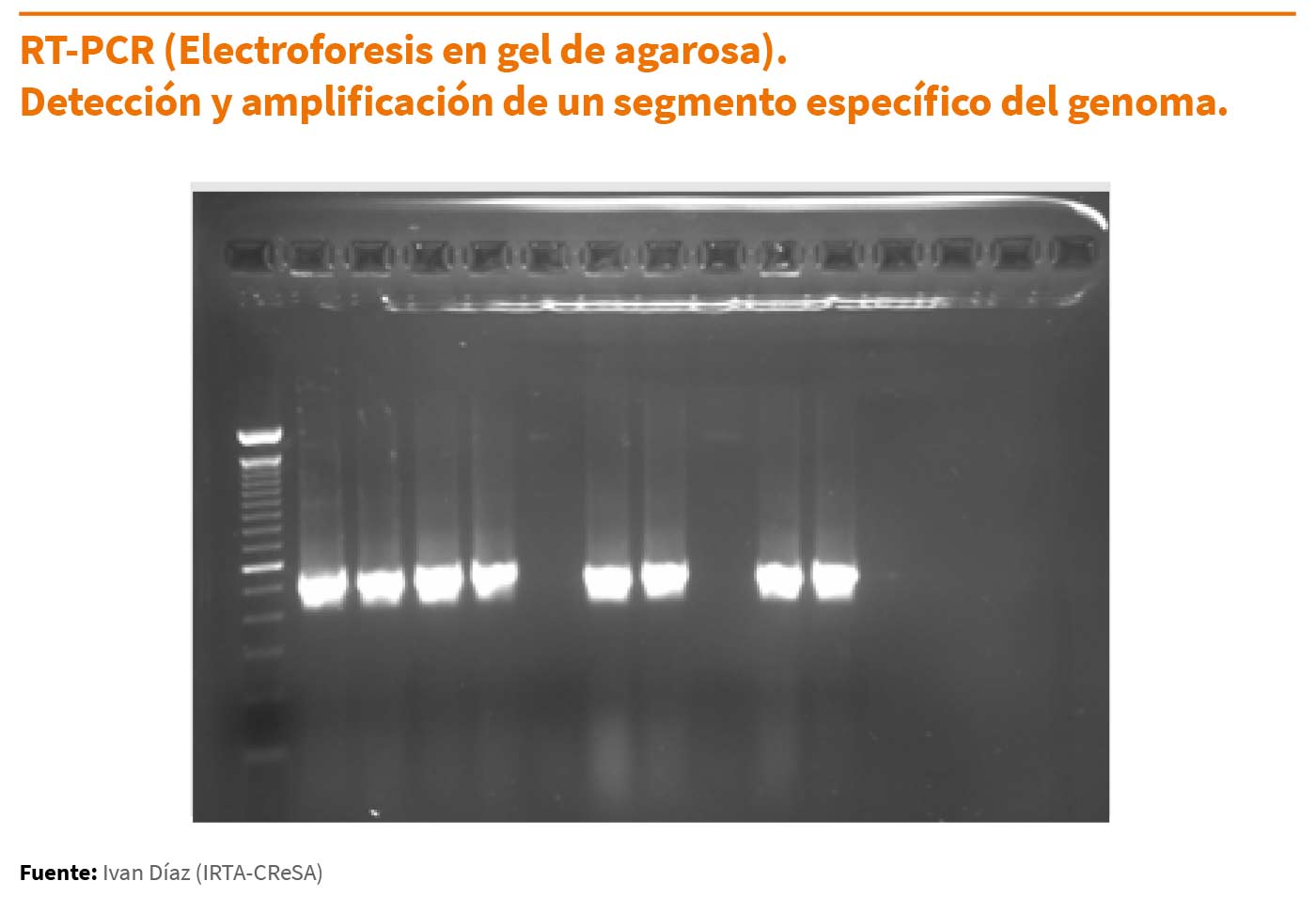

La reacción en cadena de la polimerasa con transcripción inversa (RT-PCR)

RT-PCR, junto al ELISA, es la prueba diagnóstica más comúnmente utilizada para PRRS. Se basa en la detección y la amplificación de un segmento específico del genoma. Es más sensible que el aislamiento del virus, pero como detecta el genoma, un resultado positivo no implica necesariamente la presencia de virus viable.

La RT-PCR se usa generalmente para amplificar regiones de la ORF5 y de la ORF7. Su sensibilidad es variable debido a la diversidad genética del virus. Puesto que la diversidad aumenta de forma constante, se requiere una actualización continua de los cebadores utilizados con el objeto de minimizar los resultados falsos negativos.

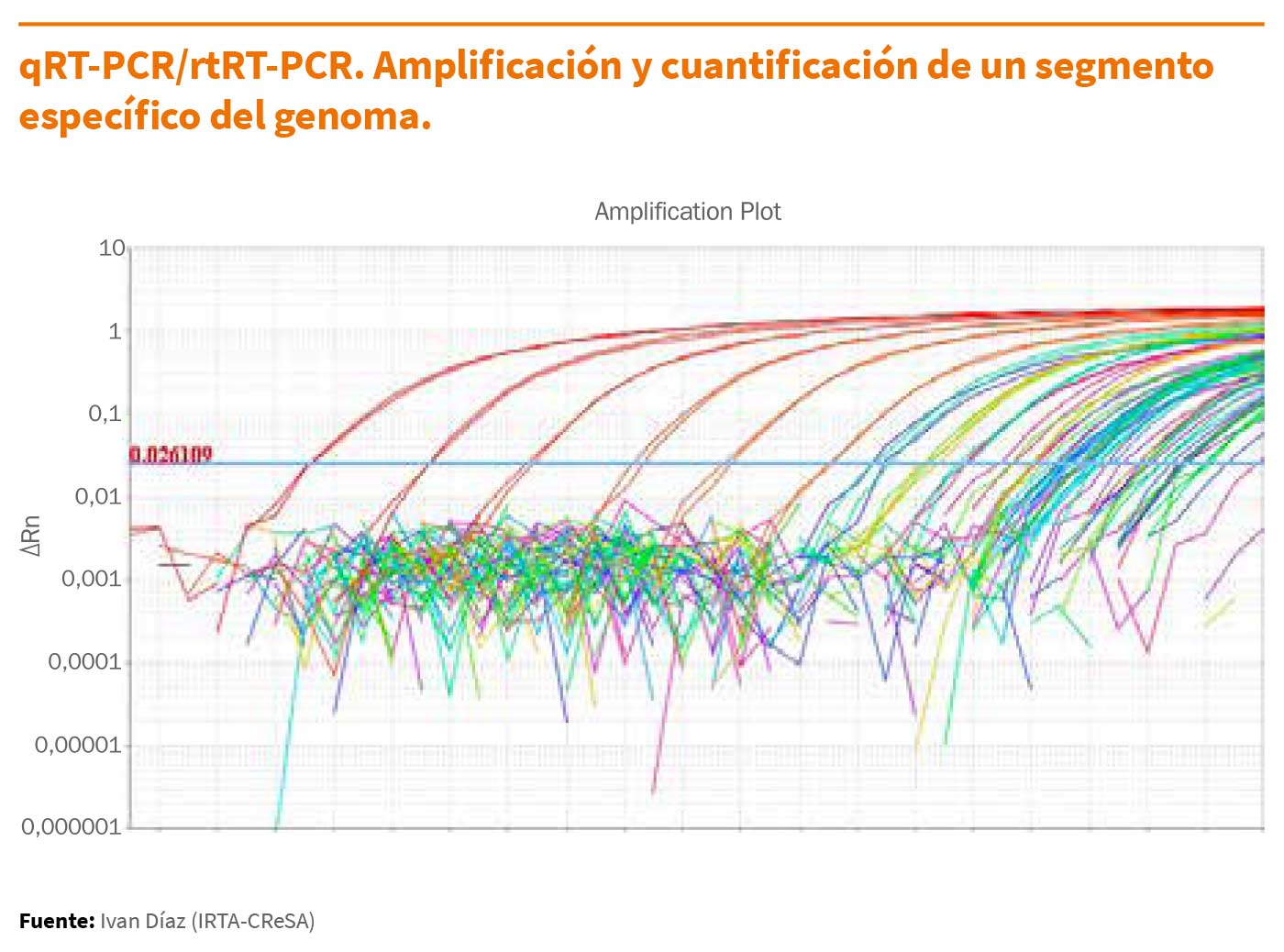

Se basa en la detección, la amplificación y la cuantificación de un segmento específico del genoma. Detecta y mide la amplificación de un segmento concreto durante cada ciclo de una reacción de PCR a tiempo real, y no al final, como ocurre en la RT-PCR convencional.

De forma breve, los oligonucleótidos marcados con un indicador fluorescente permiten la detección después de la hibridación de la sonda con su secuencia complementaria.

Mediante el instrumento de RT-PCR en tiempo real, se realiza la medición de la acumulación de la señal fluorescente. Se puede realizar una cuantificación relativa (semi-cuantificación) o absoluta del segmento objetivo.

Para realizar una cuantificación exacta, se requiere crear una línea estándar a partir de diluciones en serie de la misma cepa que intentamos detectar.

Tiempo real RT-PCR

Los resultados RT-PCR a tiempo real generalmente se muestran como valores de Ct. El valor de Ct es inverso a la cantidad de ácido nucleico que está presente en la muestra.

Puede estar exactamente (cuantificación absoluta) o aproximadamente (semicuantificación) correlacionado con el número de copias del virus presente en la muestra. Por lo tanto, los valores más bajos de Ct indican cantidades altas, mientras que los valores más altos de Ct significan cantidades bajas de ácido nucleico. Para las infecciones por el virus del PRRS, los valores típicos de Ct están alrededor de 26 ciclos, con una variabilidad significativa dependiendo de la edad del animal; los valores de Ct alrededor de 17-18 ciclos se pueden encontrar en algunos lechones virémicos recién nacidos, mientras que los valores más altos de Ct (alrededor de 26) se pueden encontrar en adultos.

En general, los valores de Ct ≥ 37 ciclos se consideran resultados con una importancia biológica relativamente baja o nula.

Las viremias debidas a las vacunaciones con virus atenuados suelen oscilar entre 30 y 35, según la cepa y la edad del animal. Todos estos valores deben ser tomados únicamente como una mera aproximación.

En la actualidad, hay disponibles ensayos comerciales de RT-PCR a tiempo real, pero aun en algunos laboratorios es un ensayo home-made. En estos últimos casos pueden existir discrepancias en los resultados entre laboratorios, ya que difieren en el diseño de cebadores, sondas…

De manera similar a la RT-PCR convencional, podría existir un número variable de falsos negativos. Por lo general, depende de la estandarización, mejora y actualización del ensayo y de la experiencia del laboratorio.

De todas formas, la sensibilidad de la RT-PCR a tiempo real es similar o ligeramente superior a la de la RT-PCR convencional, pero nuevamente se basa en la idoneidad de los cebadores con la secuencia de la muestra problema. Obviamente, la RT-PCR a tiempo real puede diseñarse para distinguir entre especies.

© Laboratorios Hipra, S.A. 2024. Reservados todos los derechos.

Ninguna parte de este sitio web o cualquiera de sus contenidos puede ser reproducida, copiada, modificada o adaptada, sin el consentimiento previo por escrito de HIPRA.

- Bautista EM, Meulenberg JJ, Choi CS, Molitor TW. Structural polypeptides of the American (VR-2332) strain of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Arch Virol. 1996:1357-65.

- Benfield DA, Nelson E, Collins JE, Harris L, Hennings JC, Shaw DP, Goyal SM, McCullough S, Morrison RB, Joo HS, Gorcyca D, Chladek D. Characterization of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome (SIRS) virus (isolate ATCC VR-2332). J Vet Diagn Invest. 1992. 4, 127-133.

- Benfield D, Nelson J, Rossow K, Nelson C, Steffen M, Rowland R. Diagnosis of persistent or prolonged porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infections Vet Res. 2000, 31:71.

- Brockmeier SL, Halbur PG, Thacker EL. Porcine respiratory disease complex. In KA Brogden, JM Guthmiller, eds, Polymicrobial Diseases. Washington, DC: ASM Press. 2002, 231-58.

- Calzada-Nova G, Schnitzlein W, Husmann R, Zuckermann FA. Characterization of the cytokine and maturation responses of pure populations of porcine plasmacytoid dendritic cells to porcine viruses and toll-like receptor agonists. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2010, 135:20-33.

- Chen WY, Schniztlein WM, Calzada-Nova G, Zuckermann FA. Genotype 2 strains of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus dysregulate alveolar macrophage cytokine production via the unfolded protein response. J Virol.2017, pii: JVI.01251-17.

- Christopher-Hennings J, Nelson EA, Hines RJ, Nelson JK, Swenson SL, Zimmerman JJ, Chase CL, Yaeger MJ, Benfield DA. Persistence of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in serum and semen of adult boars. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1995, 7:456-64.

- Cortey M, Díaz I, Martín-Valls GE, Mateu E. Next-generation sequencing as a tool for the study of Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) macro- and micro- molecular epidemiology. Vet Microbiol. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.02.002.

- Darwich L, Díaz I, Mateu E. Certainties, doubts and hypotheses in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus immunobiology. Virus Res. 2010, 154:123-32.

- Díaz I, Darwich L, Pappaterra G, Pujols J, Mateu E. Different European-type vaccines against porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus have different immunological properties and confer different protection to pigs. Virology. 2006, 351:249-59.

- Díaz I, Gimeno M, Darwich L, Navarro N, Kuzemtseva L, López S, Galindo I, Segalés J, Martín M, Pujols J, Mateu E. Characterization of homologous and heterologous adaptive immune responses in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection. Vet Res. 2012, 19:43:30.

- García-Nicolás O, Quereda JJ, Gómez-Laguna J, Salguero FJ, Carrasco L, Ramis G, Pallarés FJ. Cytokines transcript levels in lung and lymphoid organs during genotype 1 Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV) infection. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2014, 160:26-40.

- Gimeno M, Darwich L, Diaz I, de la Torre E, Pujols J, Martín M, Inumaru S, Cano E, Domingo M, Montoya M, Mateu E. Cytokine profiles and phenotype regulation of antigen presenting cells by genotype-I porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates. Vet Res. 2011, 42:9.

- Gómez-Laguna J, Salguero FJ, Pallarés FJ, Carrasco L. Immunopathogenesis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome in the respiratory tract of pigs. Vet J. 2013, 195:148-55.

- Haynes JS, Halbur PG, Sirinarumitr T, Paul PS, Meng XJ, Huffman EL. Temporal and morphologic characterization of the distribution of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) by in situ hybridization in pigs infected with isolates of PRRSV that differ in virulence. Vet Pathol. 1997, 34:39-43.

- Hill H. Overview and history of Mystery Swine Disease (swine infertility/respiratory syndrome). Proceedings of the Mystery Swine Disease Committee Meeting, Livestock Conversation Institute, Denver, CO. 1990, 29–31.

- Holtkamp DJ, Polson DD, Torremorrell M. Terminology for classifying swine herds by porcine reproductive and respiratory status. J Swine Health and Prod. 2011, 19:44-56.

- Horter DC, Pogranichniy RM, Chang CC, Evans RB, Yoon KJ, Zimmerman JJ. Characterization of the carrier state in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection. Vet Microbiol. 2002, 86:213-28.

- Loula T. Mystery pig disease. Agri-practice. 1991, 12:23–34.

- Lunney JK, Benfield DA, Rowland RR. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: an update on an emerging and re-emerging viral disease of swine. Virus Res. 2010, 154:1-6.

- Mateu E, Tello M, Coll A, Casal J, Martín M. Comparison of three ELISAs for the diagnosis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome. Vet Rec. 2006, 159:717-8.

- Mateu E, Diaz I. The challenge of PRRS immunology. Vet J. 2008, 177:345-51.

- Meier WA, Galeota J, Osorio FA, Husmann RJ, Schnitzlein WM, Zuckermann FA. Gradual development of the interferon-gamma response of swine to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection or vaccination. Virology. 2003, 309:18-31.

- Nelson EA, Christopher-Hennings J, Benfield DA. Serum immune responses to the proteins of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1994, 6:410-5.

- Appendices IV and V of the REPORT OF THE OIE AD HOC GROUP ON PORCINE REPRODUCTIVE RESPIRATORY SYNDROME Paris, 9 – 11 June 2008 http://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Our_scientific_expertise/docs/pdf/PRRS_guide_web_bulletin.pdf.

- Rodríguez-Gómez IM, Gómez-Laguna J, Carrasco L. Impact of PRRSV on activation and viability of antigen presenting cells. World J Virol. 2013, 2:146-51.

- Rovira A, Cano JP, Muñoz-Zanzi C. Feasibility of pooled-sample testing for the detection of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus antibodies on serum samples by ELISA. Vet Microbiol. 2008, 130:60-8.

- Rovira A, Clement T, Christopher-Hennings J, Thompson B, Engle M, Reicks D, Muñoz-Zanzi C. Evaluation of the sensitivity of reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction to detect porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus on individual and pooled samples from boars. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2007, 19:502-9.

- Rovira A, Reicks D, Muñoz-Zanzi C. Evaluation of surveillance protocols for detecting porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection in boar studs by simulation modeling. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2007, 19:492-501.

- Salguero FJ, Frossard JP, Rebel JM, Stadejek T, Morgan SB, Graham SP, Steinbach F. Host-pathogen interactions during porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus 1 infection of piglets. Virus Res. 2015, 202:135-43.

- Segalés J, Domingo M, Balasch M, Solano GI, Pijoan C. Ultrastructural study of porcine alveolar macrophages infected in vitro with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus, with and without Haemophilus parasuis. J Comp Pathol. 1998, 118:231-43.

- Sur JH, Cooper VL, Galeota JA, Hesse RA, Doster AR, Osorio FA. In vivo detection of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus RNA by in situ hybridization at different times postinfection. J Clin Microbiol. 1996, 34:2280-6.

- Terpstra C, Wensvoorst G, Pol JMA. Experimental reproduction of porcine epidemic abortion and respiratory syndrome (mystery swine disease) by infection with Lelystad virus: Koch’s postulates fulfilled. Vet Q. 1991, 13:131–36.

- Tian K, Yu X, Zhao T, Feng Y, Cao Z, Wang C, Hu Y, Chen X, Hu D, Tian X, Liu D, Zhang S, Deng X, Ding Y, Yang L, Zhang Y, Xiao H, Qiao M, Wang B, Hou L, Wang X, Yang X, Kang L, Sun M, Jin P, Wang S, Kitamura Y, Yan J, Gao GF. Emergence of fatal PRRSV variants: unparalleled outbreaks of atypical PRRS in China and molecular dissection of the unique hallmark. PLoS One. 200, 2:e526.

- Tong GZ, Zhou YJ, Hao XF, Tian ZJ, An TQ, Qiu HJ. Highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007, 13:1434-6.

Van Alstine WG, Popielarczyk M, Albregts SR. Effect of formalin fixation on the immunohistochemical detection of PRRS virus antigen in experimentally and naturally infected pigs. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2002, 14:504-7. - Vézina SA, Loemba H, Fournier M, Dea S, Archambault D. Antibody production and blastogenic response in pigs experimentally infected with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Can J Vet Res. 1996, 60:94-9.

- Wensvoort G, Terpstra C, Pol JMA, Lask EA, Bloemraad M, de Kluyver EP, Kragten C, van Butten L, den Besten A, Wagenaar F, Broekhuijsen JM, Moonen PJM, Zetstra T, de Boer EA, Tibben AhJ, de Jong MF, van’r Veld P, Groenland GJR, van Gennep JA, Voets MTh, Verheijden JHM, Braamkamp J. Mystery swine disease in the Netherlands: the isolation of Lelystad virus. Vet Q. 1991, 13:121–30.

- Wills RW, Doster AR, Galeota JA, Sur JH, Osorio FA. Duration of infection and proportion of pigs persistently infected with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Clin Microbiol. 2003, 41:58-62.

- Zimmerman JJ, Benfield DA, Dee SA, Murtaugh MP, Stadejek T, Stevenson GW, Torremorell M. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (porcine arterivirus). In: 10th ed. Diseases of swine, Ed. Wiley-Blackwell. 2012, 31:463-86.

Todos los derechos reservados. © HIPRA

Todos los derechos reservados. © HIPRA